Fix Your Leaking Pipeline

1. INTRODUCTION

This is part of a series of Notes related to the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) Empowering Women in Hydrography (EWiH) initiative.

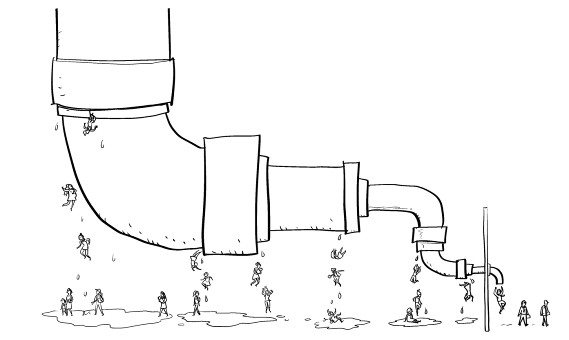

In this Note, the authors (who are listed in alphabetical order) introduce the Leaking Pipeline—the structural conditions, challenges, and lack of support in the workforce that cause women to leave the management and promotion track at higher rates than their male colleagues.

When women leave their chosen profession, they take their talent, skill, and years of experience with them. These “Leaking Pipeline” losses threaten the ability of Hydrographic Offices and related organizations to carry out their respective missions safely, in a timely manner, and with creative new ideas and innovations to carry the organizations into the future. The authors will use a combination of Personal Accounts and a review of published business research to show how Leaking Pipeline problems develop and manifest, and we examine common situations where good intentions and unconscious gender bias lead to inequitable treatment of women in the workplace. We then propose steps for the International Hydrographic Organization and member states to identify their own Leaking Pipeline problems.

In future Notes, we will explore examples of how different types of organizations identified and fixed their Leaking Pipeline problems, with suggestions on how to apply those solutions to Hydrography and its related disciplines.

2. WHAT IS THE LEAKING PIPELINE?

Multiple studies from all over the world show that diverse workforces perform better, and organizations with women in senior leadership roles have better performance in multiple ways than ones with all-male leadership. Organizations led by women, or whose board members are at least 30% women, have more success building workplace environments to support innovation (Chen et al., 2018; Ritter-Hayashi et al., 2019). Moreover, organizations led by women are more likely to constrain risks such as financial overreach or legal concerns (Perryman et al., 2015). The most recent and dramatic example of the difference made by women in leadership has been with the SARS-COV-2 pandemic: in countries led by women, fewer people died of COVID-19 and more people received social support than in countries led by men (Garikipati and Kambhampati, 2020). But although women leaders are more likely to successfully guide their organizations through serious challenges than male leaders, they are commonly promoted as a last resort or are promoted with the expectation that they will fail, something that happens often enough that it has been termed “the glass cliff” (Bruckmüller and Branscombe, 2011).

The above results beg the question – if having women in leadership positions is demonstrably advantageous to an organization, why do women receive fewer career development opportunities than men and suffer penalties for their life choices and responsibilities in ways that men do not? These disadvantages begin early in their careers and persist at every stage. The net effect is that because women encounter more barriers to career progress than men at every stage in their career path, they voluntarily depart their chosen field at higher rates than men at every career stage, leaving a relatively small number of women who can rise to senior leadership levels.

This phenomenon is known as the Leaking Pipeline.

The Leaking Pipeline is a leadership problem, not a “women” problem. Women cannot fix the Leaking Pipeline or the challenges listed above on their own, just as they cannot change their physical bodies to match the size and strength of the Reference Man discussed in the previous Note (Stewart et al., 2022).

How does the Leaking Pipeline form, and where are the main points where women choose to leave their careers?

3. The Beginnings of the Leaking Pipeline: Career Entry

When women are 27% of graduates in a field and only 15% of new hires in that field, a common finding in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) careers, that indicates gender bias in recruiting.

Multiple studies demonstrate that where hiring managers can detect gender differences (such as names on cover letters), women are judged to be less competent than men and are less likely to be hired (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012). If they are hired, women are offered lower starting salaries than their male peers for the same work. This gender bias-based behaviour is observed in both male and female hiring managers. In academia, male Principal Investigators (PIs) hire more men than women for postdoctoral positions (Sheltzer and Smith, 2014). In jobs requiring mathematical skills – a fundamental part of surveying – employers preferentially hire men instead of women, even when female candidates perform better on mathematics tests (Reuben et al., 2013).

Unconscious gender and social biases often manifest in subtle ways, rather than in overt sexism. The Personal Account below is an example of how unconscious bias de facto excluded women at the hiring stage. Even though women do participate in the activities sought after by the recruiters in the example (hunting and fishing), these are not typically activities that women will list on their resumes when job hunting.

Unconscious gender biases also manifest in the way job postings themselves are written. When job postings contain words or phrases that are socially interpreted as masculine, such as “coding ninja,” or job postings that use exclusively masculine words and pronouns to describe the desired candidate, women are less likely to apply for these positions and are less likely to be offered employment (Kuhn et al., 2020). When job postings use gender-neutral language or masculine/feminine pairs (such as “the Candidate” or “he or she”), women are more likely to both apply for a position and be hired than postings without such language (Horvath and Sczesny, 2013).

Regardless of the cause, recruitment strategies that do not address gender bias in hiring may exclude skilled, talented women before they even walk in the door.

4. The First Five Years

Entry-level women experience workplace challenges that their male peers typically do not (Kitada, 2020, and Riveia-Rodriguez, 2021). The References to this Note contain detailed information on the topics discussed here; we suggest that parties interested in further details read the original articles listed in the References in their entirety.

Safety and Quartering

The previous Empowering Women in Hydrography Note (Stewart et al., 2022) on industrial safety highlighted how women experience unequal working conditions from career onset, even though this is through no fault of their own and they may be working for organizations striving to be inclusive. The Big Three barriers to women’s physical safety in the workplace—inadequate personal protective equipment, inadequate quartering, and poorly designed equipment—create workplace environments where female employees feel undervalued or disrespected and puts them at increased risk of physical harm.

A subset of the Big Three that can have particularly far-reaching career effects is lack of quartering for women. Fieldwork and offshore work are a key part of the hydrographic survey discipline. In organizations that limit or prohibit mixed-gender living spaces such as ship’s berthing, women are steered into office-based positions. Being forbidden to join field crews as young professionals limits their promotion potential at the very beginning of their careers and it prevents women from taking opportunities that are readily available to their male counterparts.

Unsuitable quartering affects women in other ways. Women who are victims of sexual assault or harassment, whether on the job or elsewhere, may not feel physically safe living in shared quarters with men. On ships with single quarters or where women share berthing, cabins lacking security features such as door locks place women at risk of being sexually assaulted in their quarters (Ellis and Hicken, 2022). Vessel masters on ships with limited berthing may refuse to allow women to join vessel crews, as described in the Personal Account above. Asking for safety, privacy, and dignity are reasonable things for women to request, and being denied them are good reasons to find opportunities elsewhere.

Regardless of the cause, the combined effects of inadequate or unsafe quartering for women means that they will not acquire enough sea time for credentialing, will not earn offshore or hazard pay, and are held back from career advancement in ways that their male peers are not (Mobley, 2022). In a profession where field time is a key part of professional development, finding ways to improve vessel quartering is an important target for reducing the gender pay gap as well as fixing the Leaking Pipeline.

Workplace safety has more subtle effects on the Leaking Pipeline than the issues of acceptable berthing. The Personal Account below describes the experiences of a small-bodied woman who was forbidden by a reasonable and well-intentioned management policy to do a necessary part of her job. This policy puts the woman into a no-win situation: if she cannot meet her Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) without violating safety policies, and she cannot advance without meeting those KPIs, there is no possibility for promotion. For most people, the logical response to being placed into a dead-end position is to seek other opportunities.

The case study in this Personal Account is an example of how a safety problem that affects everyone (avoiding back injuries on the job) is framed as a women’s problem. Under this framing, the work of addressing the unintended consequences (being held back from learning experiences) is placed on the people who are most burdened by the policy. Women, especially entry-level women with neither the authority nor the responsibility to manage field operations, cannot and should not be expected by leadership to address this problem on their own. In this instance, the organization changed its safety policy to give field parties carts and lifting devices, protecting all employees from workplace back injuries whilst allowing its employees fair opportunities.

Group Threat, Early-Career Mentoring, and the Conversations That Stop

Group Threat is the perception by a dominant group that an outside group is challenging their privilege and status. The dominant group will react to those perceived threats in ways that have consequences for the outside or minority group. The consequences of the reaction to perceived threats vary in severity from subtle exclusion or isolation to violence. Group Threat is a common human social behaviour pattern that is found in all societies and cultures (Land et al., 2021).

For the purposes of this Note, we will focus exclusively on Group Threat behaviours related to a proportionally large number of men and proportionally small number of women. We acknowledge that people who are members of a second minority group, such as ethnic or linguistic, face different problems; it is beyond the scope of this Note to explore them. Reactionary behaviour on the part of men to women’s participation in the Hydrographic workplace puts these women at a disadvantage, even if these reactionary behaviour patterns are unintentional.

A subtle manifestation of Group Threat in the Hydrographic workplace is among its most common: groups of men ceasing to speak amongst each other when a woman enters their work area. This is a reaction to the perception that a woman might accuse one of the men of inappropriate behaviour. The result for the women is feeling isolated or cut off from socializing with the remainder of the crew. A similarly subtle manifestation is discussed in the Personal Account below:

because the male officers perceived that giving timely, constructive criticism to a young female officer would make them appear sexist, these officers reacted by not offering useful or timely criticism at all.

In both instances, Group Threat behaviours set up a self-fulfilling cycle: to avoid being perceived as sexist or as a sexual harasser, men do not offer the support or constructive feedback to junior women in their group that they do to junior men. The junior men under their mentorship develop career skills faster than the women, which reinforces the senior mens’ perception that junior women have lower potential for advancement than their male peers. Not receiving constructive criticism or mentorship is problematic—people will not develop professionally without guidance—and thus the direct consequence of men’s perception of risk is that their women subordinates do not receive the same career development opportunities as their male peers. Telling women to “be more confident” or to ask for guidance will not remove these career barriers for the simple reason that it is impossible for women to change the thoughts or reactions of their male colleagues. In the Personal Account, the ensign in question did ask her male superiors for guidance, repeatedly. The underlying problem is that the men on her ship perceived that criticizing her performance was a risk, and they avoided that perceived risk to themselves at her expense.

A far less subtle manifestation of Group Threat is bullying or harassment at work. A recent literature review found that an average of 1 out of every 5 women seafarers reported being sexually harassed by shipmates, with some reports in the review finding that half of women seafarers reported sexual harassment (Österman and Boström, 2022). Gender diversity research has found that men who strongly self-identify as a dominant group in the workplace (e.g., “it’s a man’s industry”) are more likely to harass or bully their women colleagues than peers who do not identify as such (Jones et al., 2022). “Othering” or harassing a member of a minority group reinforces the harasser’s position as a member of the majority group while simultaneously marginalizing the member of the minority group.

These challenges take their toll: young professional women cite feeling unsupported, undervalued, underpaid, or bullied as key reasons why they leave their jobs (Gotara, 2022). Although we were unable to find specific statistics for Hydrography and related hydrospatial disciplines, in general, 40% of women left their STEM careers within 5 years of entry.

5. More Leaks, Fewer Opportunities: Five to Fifteen Years of Career Tenure

As careers progress beyond the five-year mark, it is expected that people will voluntarily switch career tracks. In Hydrography, the period between five and ten years typically coincides with field-based surveyors choosing to take office-based jobs, which in turn spurs lateral motion into affiliated disciplines such as sales, working as a client representative, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Computer Aided Drafting (CAD) specialists, or land-based survey work. In academia, this is the point where people shift from postdoctoral research to tenure track or leave for other career paths.

For women, however, the early effects of the Leaking Pipeline combined with the accumulated effects of gender bias and changing roles in life create more points where women will choose to leave their careers at higher rates than men. There are three overarching reasons women cite for leaving at the five-to-ten-year point (Foster, 2018):

- Care work responsibilities outside the paid workforce, particularly of children;

- Not being selected for promotion from entry-level to first-level management;

-

Lack of mentoring and support from superiors.

Childbearing and Caregiving

The birth of a child is typically the first of a cascade of events that culminates in almost half of first-time mothers leaving their STEM careers, switching to part-time work, or leaving the labour force entirely.

Having children is a normal and natural thing for humans to want to do. The desire to be a parent is not constrained by gender – nor are the career consequences. Two out of every five new mothers and one out of every five new fathers leave STEM fields after their first child is born. That so many parents depart their STEM careers to attend to family responsibilities points to structural problems in organizational leadership. Organizations that require extended family separation (such as life at sea) or demand continuous overtime force people to choose whether and how to divide their time between family responsibilities and their demanding careers. Particularly for military or uniformed service members, this is a strong incentive to resign, such as in the Personal Account below.

Parenthood is such a large factor in wage inequity that it is termed “The Motherhood Penalty.” Research on parental income in European nations shows that while motherhood correlates strongly with wage and economic losses over time, men who remain childless have steady wages while non-caretaking fathers experience wage growth (Gari, 2019). Early-career gender wage inequities are exacerbated by the Motherhood Penalty, which leads to another leakage point: if a parent leaves the paid workforce to do unpaid care work, it is usually the person paid less. For opposite-sex couples, this is almost always the woman.

The Motherhood Penalty begins during pregnancy, continues after birth, and increases after each new child. The Motherhood Penalty is not limited to financial gains or losses. Unconscious biases against the perceived abilities of mothers or commitment to remaining in the workforce leads to women being undervalued and facing double standards in performance. Men with children who are not primary caregivers are not penalized during hiring, but women with children are (Benard et al., 2008). Unconscious biases about pregnancy and safety, even when well-meaning such as the Personal Account below, exclude pregnant women and mothers and limit their career development opportunities.

Interestingly, while the Motherhood Penalty is a financial and career burden to women, it is not necessarily a social burden. Women who are mothers and involved in caregiving do not challenge stereotypical gender roles, and therefore they are not subjected to gender-based harassment (including sexual harassment) as often as women who are not mothers or women with dependents who are not the primary caregiver (Berdahl and Moon, 2013). This finding highlights the nuanced nature of structural gender bias in the workplace: by conforming to feminine gender norms, caregiving women are less likely to be harassed and more likely to be perceived as warm and competent – but also less likely to be paid equitably for their work and much less likely to be considered for promotion.

In our efforts to point out how gender biases affect the ability of Hydrographic Offices to recruit and retain talented people to fulfill their respective missions, we would be remiss if we did not explore how primary caregiving affects men. In the wake of a global viral disease outbreak responsible for the deaths of nearly 1 out of every 500 humans on the planet in only two years (WHO, 2022), the mothers of about 1.9 million children worldwide died of COVID-19 and the mothers of millions more are disabled by Long Covid (Unwin et al., 2022). For many, their fathers are now their primary caregivers. While the effects of a global pandemic will linger for decades, bereavement is not the only reason that men do care work. Divorced fathers with primary custody do care work for their children, and men do care work for elderly parents or ill relatives.

Unfortunately, research shows that male caregivers are more likely than non-caregivers to be given poor reviews, demoted, or made redundant— termed “Fatherhood Forfeits”—that in some cases are harsher than the Motherhood Penalty (Vandello et al., 2013; Mar and Sussman, 2020). Men who ask for flexible work hours receive lower hourly wage raises than non-caregivers (Rudman and Mescher, 2013). Male caregivers report being mocked, perceived as idle, or being subject to intrusive oversight under the assumption that they are using caregiving duties as an excuse to avoid other work (Kelland et al., 2022). This is a variation on Group Threat behaviour: caregiving is socially coded as a feminine task. Men who enter caregiving roles threaten the perceived gender privileges of other men, and as a result, male caregivers are harassed or bothered at work by their colleagues (Berdahl, 2013). Like their female colleagues, men who are subjected to gender-based harassment are more likely to quit their jobs and find a better environment elsewhere.

These Fatherhood Forfeits and the Motherhood Penalty are structural and social workplace issues penalizing caregivers, and the scaffold upon which those structural issues rest is the concept that caregiving is a feminine-gendered task. The normal, necessary care work that successful societies require is framed as a women’s workplace problem, not as a problem that affects all people doing caregiving. If organizations make comprehensive changes to support all caregivers—including caring for elders or disabled persons as well as children—those organizations’ ability recruit and retain talented women will increase accordingly.

Missing the First Promotion, Mentoring, and Mini-Me

For women to rise through the career ranks to senior leadership, they must first be promoted to first-level management positions. This first step is a major tripping point: Kinsey Institute studies from 2017 to 2021 consistently show that women in technical or STEM fields are 52% less likely to be promoted to first-level management than their male peers (McKinsey & Company, 2017, 2021). If only that first-level gap could be closed, the number of women in management in the USA alone would increase to over 1 million women in only a few years.

To some extent, caregiving is a factor in why women don’t make the first step. Taking time off for caregiving does play a role in who is offered career development opportunities (below), who is promoted, and who stays in the same place.

The magnitude of the difference between men and women being promoted cannot be explained only by caregiving. These women who stay and who ask for promotion are less likely to be interviewed and they receive fewer promotions than men with similar credentials. Business research calls this phenomenon the “Gender Promotion Gap”.

Up to half of the gender promotion gap can be accounted for when controlling for two related causes:

- Men are promoted based on potential and women on performance

- Confident men are perceived to be likable and competent, whereas confident women are perceived to be unlikable—and the greater the woman’s level of excellence, the greater the probability she is considered unlikable (Hill et al., 2010)

Potential is a matter of perception, and perceptions of career potential are gendered (Player et al., 2019). More broadly, men are perceived to have better ability to take on high-performing tasks than women (a measure of business potential), even when their female peers have equal or superior performance records (Benson et al., 2022). Women who receive high performance scores during one review cycle and high achievement in the next performance review cycle are still rated as having lower potential, in spite of their consistent performance (Shue, 2021). High-performing women who do not fit into ideals of how women should look or behave in the office are likewise rated as having lower promotion potential—a particular disadvantage for women who are ethnic or racial minorities.

Perceptions of potential are exacerbated by lack of development and mentoring for women. Multiple factors based in gender bias and lack of representation limit women’s mentoring opportunities relative to their male peers. The relative dearth of women in higher management leaves few role models for women who are junior to them and few opportunities for a junior woman to be mentored or sponsored by a more senior woman. Earlier in this Note we examine a situation where unconscious biases create a self-fulfilling prophecy where men who receive more mentorship than women are perceived to have more development potential than women who are excluded from it. This happens at higher levels via Affiliation bias, also known as “Mini-Me Syndrome.” Mini-Me Syndrome occurs when people choose to mentor people like themselves, such as white men mentoring other white men but not women of any race or minoritized men (Grant, 2018). Women in workplaces without women represented in leadership positions will rightfully question if they will be considered for promotions by the same male staff who do not offer them equitable mentoring or exclude them from career development opportunities.

Likeability, another commonly-cited barrier to women rising to managerial positions, is similarly a matter of perception. Characteristics associated by men with good managers – confidence, assertiveness, ambition, and charisma – are associated with men and male leadership styles. Women can develop and cultivate these traits, but at a cost: women who assert themselves are called bossy, shrill, shrewish, or bitchy, all gendered insults that are almost never applied to heterosexual men (Maloney and Moore, 2020). Women who are not perceived as warm and nurturing (stereotypical feminine gender traits) are not perceived as competent or likeable (Mayo, 2016), while women who are outspoken and confident in their abilities as well as very competent are perceived as cold and especially unlikable. In one study, a third of women who described themselves as self-promoting (such as asking for performance bonuses or promotions to leadership positions) reported backlash or punishment for that behaviour (Williams et a, 2014). If women who develop leadership traits valued in men are thought of as unlikeable or as poor leaders, it logically follows that the perceived leadership potential of these women will be lower. These things together set up another negative feedback loop: receiving backlash for breaking gender role stereotypes and teaches competent women who assert themselves that they will be punished for that behaviour, which in turn decreases their confidence that they will be offered leadership positions if they apply for them (Guillén et al., 2016).

A 2016 study from the Society of Women Engineers reports that when women feel that there are unnecessary and arbitrary burdens to advance in their careers (e.g., have to demonstrate nurturing behaviour to colleagues) and to their promotion potential (e.g., have exceptional documented performance but low potential ratings), they choose to leave for another career at higher rates than men (Zazulia, 2016). Women who do stay in their career path but do not choose to apply for managerial positions do not necessarily lack confidence in themselves – more often, they lack confidence in the system they are working in.

6. Fifteen Years and Beyond: Approaching Senior Leadership

The combined effects on women of conscious and unconscious gender biases, self-fulfilling cycles, potential over performance, the Motherhood Penalty, gendered language choices, and punishment for behaving in stereotypically masculine ways persist in the step from middle to senior management, transported in the minds and memories of everyone else in the Leaking Pipeline. In the absence of deliberate pipeline interventions from organizational leaders, it is unreasonable to expect that the humans applying for promotions or sitting on selection boards will examine their behaviours and change them. As people approach organizational senior leadership positions, numbers alone become a reason why women are not promoted to senior positions. Senior leadership positions require specific skill sets and experience. If there are no women in a potential hiring pool with those qualifications, then only men will be hired for those positions. This is especially pronounced in organizations with closed entry pipelines, such as uniformed service Hydrographic Offices.

Business research has determined some additional factors that hold women back from the climb to senior management. Research by Harvard Business Review found that during performance evaluations, men were given specific feedback relative to both their achievements and to what development they needed, while women were given vague, unspecific feedback without specific development items (Correll and Simard, 2016). When women did receive feedback, it frequently focused on communication (e.g., “your speaking style is too aggressive”) and not on linking specific operational, technical, or business tasks to their overall performance. Giving men detailed feedback without prompting while requiring women to solicit their managers to give them specific feedback for improvement is an echo of the Personal Account by an entry-level ensign: regardless of why a woman is not getting feedback, she cannot make improvements if her superiors will not tell her what she needs to improve. This matters for promotion—recall that women must have superior performance records to be considered to have equal potential to their male colleagues, and not being able to link specific organizational tasks to her performance makes it difficult for women (or selection boards) to make a case for her promotion.

Senior women seeking promotions are subject to a particular type of gender-related barrier that junior women are not: the Glass Cliff. Broadly speaking, the Glass Cliff is the phenomenon of appointing women to senior management roles when an organization is experiencing a crisis, making their positions precarious and the chance of failure high. Research in executive officers of Fortune 500 companies show that firms experiencing performance declines are more likely to promote women to Chief Executive Officer—and then replace them with white men after as little time as a year if the company performance does not improve under a woman’s leadership (Cook and Glass, 2013). The concept of the Glass Cliff is relatively new, first researched in 2003, and research into how it develops is ongoing. Regardless of the human behaviour behind it, the Glass Cliff is a substantial barrier for the few women remaining in the Leaking Pipeline to ascend to executive roles.

At the end of the pipeline, the proof is in the numbers. Fewer than ten nations out of approximately one hundred member states in the hundred years that the IHO has existed have now or had previously a woman as their chief hydrographer, and no women served as chief hydrographer prior to the year 2000.

7. So Now What? Suggested Next Steps for the IHO and Member State Hydrographic Offices

The heart and soul of the Empowering Women in Hydrography project is about fulfilling our collective mission as Hydrographers of mapping the world’s oceans and providing data for the benefit of people around the world. If we as a group do not support and cultivate the talents, skills, and creativity of women in Hydrography and hydrospatial disciplines, we are in effect hobbling the success of our own mission.

The authors of this Note included the anonymized Personal Accounts to put human faces and human experiences into an otherwise dry academic-style editorial. These Personal Accounts are all based on real-life experiences from people who wanted to help improve these situations for future generations. Collectively, we heard so many Personal Accounts that we could write an entire document of them alone. We felt that we could not tell some stories because there is no way they could be anonymized enough to prevent potential embarrassment or retaliation against the woman involved. Other stories are presented almost word-for-word of what these women told us, with only their names changed for privacy. These stories are clear evidence that gender bias and harmful gender stereotypes exist at every level, that they affect men as well as women, and that they are systemic problems that are greater in breadth or depth than any one person’s sincere efforts can mitigate.

That being said, the plural of “anecdote” is not “data.” Throughout this Note, the authors reference literature studying STEM disciplines in general; the disciplines of engineering, mathematics, and physics; workforce sectors other than STEM; and global trends in women’s career attainment and the Leaking Pipeline. What we do not have – and were not able to find – is sufficiently detailed quantitative data to determine the scope of the Leaking Pipeline problem in Hydrographic Offices or related organizations in academia or the private sector. Without that data, it is impossible to identify pipeline leaks specific to Hydrography or to create specific mitigations to them.

The authors acknowledge that we and the references we have collected are overwhelmingly WEIRD: they are almost all written by people living in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic nations. We do not have enough data to understand the scope of the Leaking Pipeline in Middle-Income or Lower-Income Countries, and we do not have data to understand the effects of the Leaking Pipeline in nations whose academic and industrial literature is published in languages the authors do not speak.

We therefore suggest that the IHO create a questionnaire for member states and other interested organizations to gather relevant data on equity in recruiting, mentoring, retaining, promo-ting, and paying women.

The questionnaire could be distributed to representatives of member states during Capacity Building meetings and collected after a predetermined time frame (we suggest that six months is reasonable to create the questionnaire).

Suggested lines of inquiry:

1. Conduct a jobs audit for the last 10 years.

- How many women were hired at/promoted to each career level?

- What percentage of women were hired at each career level?

- How many women were hired for technical roles vs. non-technical?

- In that time, what is women’s retention and what is men’s?

- How many women were promoted to management or acting roles?

- Are there any confounding factors (such as closed pipelines for military or uniformed service Hydrographic Offices)?

- If hiring data exists, how many women were interviewed for each new hire in the past year, compared to how many men?

- Review job postings for gendered or gender-neutral language.

2. Conduct a pay audit for current employees.

- Compare how men and women are paid for doing similar work, controlling for educational level, work experience, or specialized training.

- If the parenthood status is known, compare pay for parents vs. childless individuals and for employees who use flex time vs. ones who do not.

- Examine non-wage compensation such as time off, stock options, or retirement plans for gender parity.

3. Create a confidential employee interview on unconscious bias and discrimination, preferably administered by an outside agency.

- Ask employees if they feel like they have been discriminated against or have experienced bias in the past five years, and if so, how.

- Age, race or ethnic origin, spoken language, religion, or caregiving status.

- Ask employees what mentorship and leadership development opportunities they have been given.

- Give employees a space to write their stories down. Common themes in different individuals’ stories help identify larger-scale problems.

- Analyze employee performance reviews for gendered language, specific developmental feedback, and vague statements without specific language.

After member states have submitted data on their pipelines, the IHO Capacity Building committee can analyze that data, or hire a third party to do so on its behalf. We recommend partnering with an organization that has worked on Leaking Pipeline topics in the past, such as institutions listed in the References.

We suggest that data be categorized and compared according to the following factors:

- Global Aggregate

- Geographic and/or Cultural Regions

- Country Income (High, Upper-Middle, Lower-Middle, Low)

- Type of Hydrographic Office (Civilian, Military/Uniformed Service, Mixed)

The results of the Leaking Pipeline study could be posted on the IHO website and made public in future editions of the International Hydrographic Review.

We are Hydrographers. We are surveyors, scientists, and engineers. We acquire data about the world around us and follow the data where it leads us. The data overwhelmingly shows that organizations with diverse representation, especially of women, leads to better overall performance. Human behavioural factors such as Group Threat and unconscious gender biases prevent women from participating equitably in our organizations. We have the power to choose to follow the data that directs us to elevate our mission by supporting and elevating the women in our ranks – and by fixing the Leaking Pipelines that disproportionately force them out.

We should do so.

8. References

Benard, S., Paik, I., and Correll, S.J. (2008). Cognitive Bias and the Motherhood Penalty. Hastings Law Journal 59 (6). Accessed August 6, 2022 at https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol59/iss6/3

Benson, A., Li, D., and Shue, K. (2022). “Potential” and the Gender Promotion Gap*. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://conference.nber.org/conf_papers/f157211.pdf

Berdahl, J.L., and Moon, S.J. (2013). Workplace mistreatment of middle class workers based on sex, parenthood, and caregiving. Journal of Social Issues, 69 (2), pp. 341-355. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12018

Blau, F.D. and Devaro, J. (2007). New Evidence on Gender Differences in Promotion Rates: An Empirical Analysis of a Sample of New Hires. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 46: 511-550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2007.00479.x

Bruckmüller, S., and Branscombe, N.R. (2011). How Women End Up on the ‘Glass Cliff. Harvard Business Review, January-February 2011. https://hbr.org/2011/01/how-women-end-up-on-the-glass-cliff

Cech, E.A., and Blair-Loy, M. (2019). The changing career trajectories of new parents in STEM. PNAS 116 (10), pp. 4182-4187. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.181086211

Chen, J., Sau Leung, W., and Evans, K.P. (2018). Female board representation, corporate innovation, and firm performance. Journal of Empirical Finance, 48, pp 236-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2018.07.003

Chiricos, T.G., Pickett, J.T., and Lehmann, P.S. (2020). Group Threat and Social Control: A Review of Theory and Research. In: Criminal Justice Theory: Explanations and Effects. Routledge, 2020. DOI:10.4324/9781003016762-4

Cook, A. and Glass, C. (2014). Above the glass ceiling: When are women and racial/ethnic minorities promoted to CEO? Strat. Mgmt. J., 35 pp. 1080-1089.https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2161

Correll, S.J. and Simard, C. (2016). Research: Vague Feedback is Holding Women Back. Harvard Business Review, April 29, 2016. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://hbr.org/2016/04/research-vague-feedback-is-holding-women-back?ab=at_art_art_1x4_s03

Ellis, B., and Hicken, M., (2022). Two students sue shipping giant Maersk, alleging sexual assault and harassment. CNN News, accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://www.cnn.com/2022/06/15/business/maersk-rape-lawsuits-students-invs/index.html

Foster, T., Klein, A.B., Gee, J. (2018). The Pipeline Predicament: Fixing the Talent Pipeline. Gloria Cordes Larson Center for Women and Business, Bentley University, Waltham, USA. Accessed on 6 August 2022 at https://www.bentley.edu/centers/center-for-women-and-business/cwb-pipeline-report?submissionGuid=b2b8925e-9ce0-4f4e-8d25-2dfc32a2e5b8

Garikipati, S., and Kambhampati, U. (2020). Leading the Fight Against the Pandemic: Does Gender Really Matter? SSRN, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3617953

Gotara (2022). Brain Drain: Why do STEM Women Quit or Stagnate? It’s Not for the Reasons You Think. Accessed on 8 August 2022 at https://www.gotara.com/why-stem-women-quit-or-stagnate-in-their-job/

Grant, G. (2018). Similar-To-Me Bias: How Gender Affects Workplace Recognition. Forbes, August 7, 2018. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://www.forbes.com/sites/georginagrant/2018/08/07/similar-to-me-bias-how-gender-affects-workplace-recognition/?sh=411ea570540a

Guillén, L., Mayo, M, and Karelaia, N. (2016). The competence-confidence gender gap: Being competent is not (always) enough for women to appear confident. Academy of Management Conference, Anaheim, California, USA, 2016. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://www.margaritamayo.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The-competence-confidence-gender-gap.pdf

Hill, C., Corbett, C., and St. Rose, A. (2010). Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. AAUW, Washington DC, USA. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED509653.pdf

Horvath, L.K. and Sczesny, S. (2013). Reducing women’s lack of fit with leadership positions? Effects of the wording of job advertisements. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25 (2), pp. 316-328. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1067611

Jones, A., Turner, R.N., and Latu, I.M. (2022). Resistance towards increasing gender diversity in masculine domains: The role of intergroup threat. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 25 (3), pp. 24-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211042424

Kelland, Jasmine, Lewis, Duncan, and Fisher, Virginia. 2022. Viewed with Suspicion, Considered Idle and Mocked-Working Caregiving Fathers and Fatherhood Forfeits. Gender, Work & Organization 1– 16. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12850

Kitada, M. (2021). Women Seafarers: An Analysis of Barriers to Their Employment. In: Gekara, V.O., Sampson, H. (eds) The World of the Seafarer. WMU Studies in Maritime Affairs (9). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49825-2_6

Kuhn, P., Shen, K., and Zhang, S. (2020). Gender-targeted job ads in the recruitment process: Facts from a Chinese job board. Journal of Development Economics 147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102531

Lang, M., Xygalatas, D., Kavanagh, C. M., Boccardi, N., Halberstadt, J., Jackson, C., Martínez, M., Reddish, P., Tong, E. M. W., Vázquez, A., Whitehouse, H., Yamamoto, M. E., Yuki, M., and Gomez, A. (2021). Outgroup threat and the emergence of cohesive groups: A cross-cultural examination. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211016961

Mar, R.T. and Sussman, D. (2020). Men Are Being Fired for Being Caregivers. Here’s Why that Hurts Women Too. American Civil Liberties Union, New York, USA. Accessed on August 6, 202 at https://www.aclu.org/news/womens-rights/men-are-being-fired-for-being-caregivers-heres-why-that-hurts-women-too

Mari, G. (2019). Is there a Fatherhood Wage Premium? A reassessment in Societieswti Strong Male-Breadwinner Legacies. Journal of Marriage and Family 81 (5), pp. 1033-1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12600

Moss-Racusin, C., Dovidio, J.F., Brescoll, V.L., and Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. PNAS 109 (41), pp. 16474-16497. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1211286109

Maloney M.E. and Moore P. (2019) From aggressive to assertive. Int J Women’s Dermatology 6(1), pp. 46-49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.09.006.

Mayo, M. (2016). To Seem Confident, Women Have to Be Seen as Warm. Harvard Business Review, July 8, 2016. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://hbr.org/2016/07/to-seem-confident-women-have-to-be-seen-as-warm

McKinsey & Company (2017). Women in the Workplace 2017. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://wiw-report.s3.amazonaws.com/Women_in_the_Workplace_2017.pdf

McKinsey & Company (2021). Women in the Workplace 2021. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://leanin.org/women-in-the-workplace-report-2021

Mobley, I. (2022). Breaking the Bias: Closing the Gender Pay Gap. Ocean Infinity, accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://oceaninfinity.com/breaking-the-bias-closing-the-gender-pay-gap/

Österman, C. and Boström, M. (2022). Workplace bullying and harassment at sea: a structured literature review. Marine Policy 136, Kalmar Maritime Academy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104910

Player, A., Randsley de Moura, G., Leite, A.C., Abrams, D., and Tresh,F. (2019). Overlooked Leadership Potential: The Preference for Leadership Potential in Job Candidates Who Are Men vs. Women. Front. Psychology, 16 April 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00755

Perryman, A.A., Fernando, D., and Tripathy, A. (2015). Do gender differences persist? An examination of gender diversity on firm performance, risk, and executive compensation. Journal of Business Research, 69 (2), pp 579-586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.05.013

Ritter-Hayashi, D., Vermeulen, P., Knoben, J. (2019). Is this a man’s world? The effect of gender diversity and gender equality on firm innovativeness. PLoS ONE, 14 (9): e0222443. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222443

Reuben, E., Sapienza, S., and Zingales, L. (2014). How stereotypes impair women’s careers in science. PNAS 111 (12), pp. 4403-4408. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1314788111

Rudman, L.A. and Mescher, K. (2013). Penalizing Men Who Request a Family Leave: Is Flexibility Stigma a Femininity Stigma?. Journal of Social Issues, 69: 322-340. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12017

Rivera-Rodriguez, A., Larsen, G., Dasgupta, N. (2022). Changing public opinion about gender activates group threat and opposition to feminist social movements among men. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 25 (3), pp. 811-829. doi:10.1177/13684302211048885

Sheltzer, J.M., and Smith, J.C. (2014). “Elite male faculty in the life sciences employ fewer women.” PNAS 111 (28), pp. 10107-10112. https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.1403334111

Shue, K. (2021). Women Aren’t Promoted Because Managers Underestimate Their Potential. Yale Insights, 2021. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/women-arent-promoted-because-managers-underestimate-their-potential

Stewart, H.F., Imahori, G., Biron, A., and Bhatia, S. (2022). Empowering Women in Hydrography: Safety First! International Hydrographic Review 27, pp. 121-131. https://ihr.iho.int/articles/empowering-women-in-hydrography-safety-first/

Unwin, J.T., Hillis, S., Cluver, L., Flaxman, S., Goldman, P.S., Butchart, A., et al. (2022) Global, regional, and national minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and caregiver death, by age and family circumstance up to Oct 31, 2021: an updated modelling study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 6 (4), pp. 249-259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00005-0

Vandello, J.A., Hettinger, V.E., Bosson, J.K. and Siddiqi, J. (2013), When Equal Isn’t Really Equal: The Masculine Dilemma of Seeking Work Flexibility. Journal of Social Issues, 69: 303-321. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12016

Williams, J.C., Phillips, K.W., and Hall, E.V. (2014). Double Jeopardy? Gender Bias Against Women in Science. WorkLifeLaw, Hastings, California, USA. Accessed August 6, 2022 at https://worklifelaw.org/publications/Double-Jeopardy-Report_v6_full_web-sm.pdf

World Health Organization (2022). Global excess deaths associated with COVID-19, January 2020-December 2021. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://www.who.int/data/stories/global-excess-deaths-associated-with-covid-19-january-2020-december-2021

Zazulia, N. (2016). Women Leave STEM Jobs for the Reasons Men Only Want To. U.S. News and World Report, April 8, 2016. Accessed on August 6, 2022 at https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-04-08/study-women-leave-stem-jobs-for-the-reasons-men-only-want-to