As we celebrate GEBCO’s 120 years of ocean discovery (1903–2023), we do so in a situation and in an environment that has drastically changed since our last celebration twenty years ago. We are one of the longest-running ocean mapping data collection, compilation, and distribution programmes in history. And yet, even after more than a century of activities, we are still only at the beginning of Earth’s last great mapping endeavour.

Recent years have seen a rise in ocean exploration, which has led to the discovery of previously untapped natural resources, new medicines, genomes, and food sources. But how do we manage and use these discoveries fairly and sustainably? The 30×30 Project calls for world leaders to commit to protecting at least 30 % of the world’s ocean by 2030 through a network of highly protected marine areas. And yet, ocean and coastal territories must be well-defined so nations can decide how to protect and monitor the region effectively. We cannot manage what we do not know is there. This simple fact will become increasingly important as nations venture further into the ocean to build their blue economies.

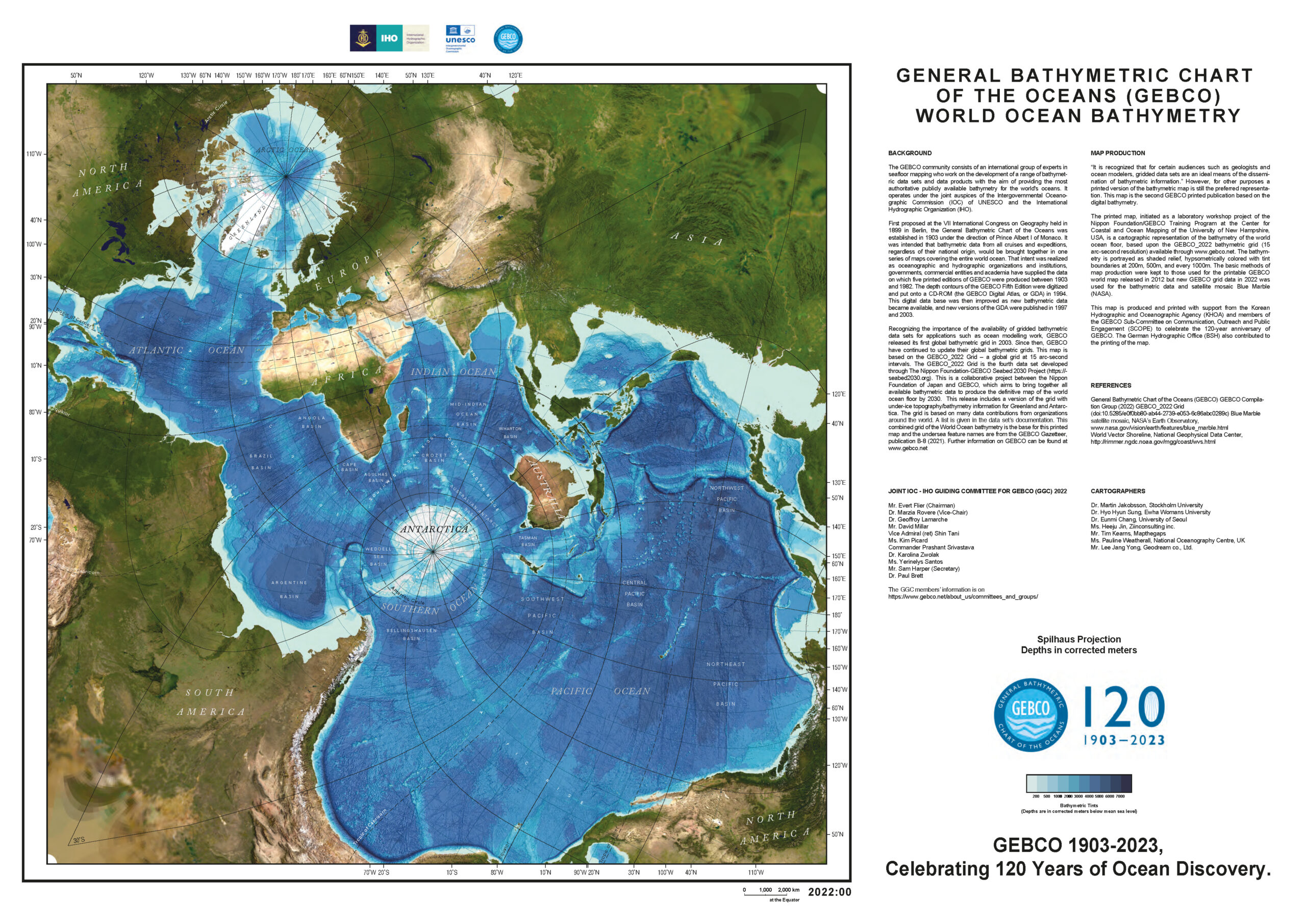

The challenge of coordinating global mapping efforts and making available ocean depth data (also known as bathymetry data) to the public has been the primary objective of GEBCO since its genesis.

There are many benefits to having a complete map of our ocean. The shape and depth of the seafloor are foundational knowledge we need to address many ocean issues brought to the world stage by initiatives such as The Paris Agreement, The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030), the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) and, just recently, the historic new UN High Seas Treaty, protecting international waters. Each of these initiatives has highlighted the need for comprehensive global seabed information as a critical component for achieving their objectives. Knowing the shape of the seabed is critical to understanding the circulation of ocean currents and associated effects on climate change, weather systems, tides, and tsunami wave propagation. Improving our knowledge of the seabed will allow us to better prepare for and mitigate possible impacts of a changing climate, and protect marine life.

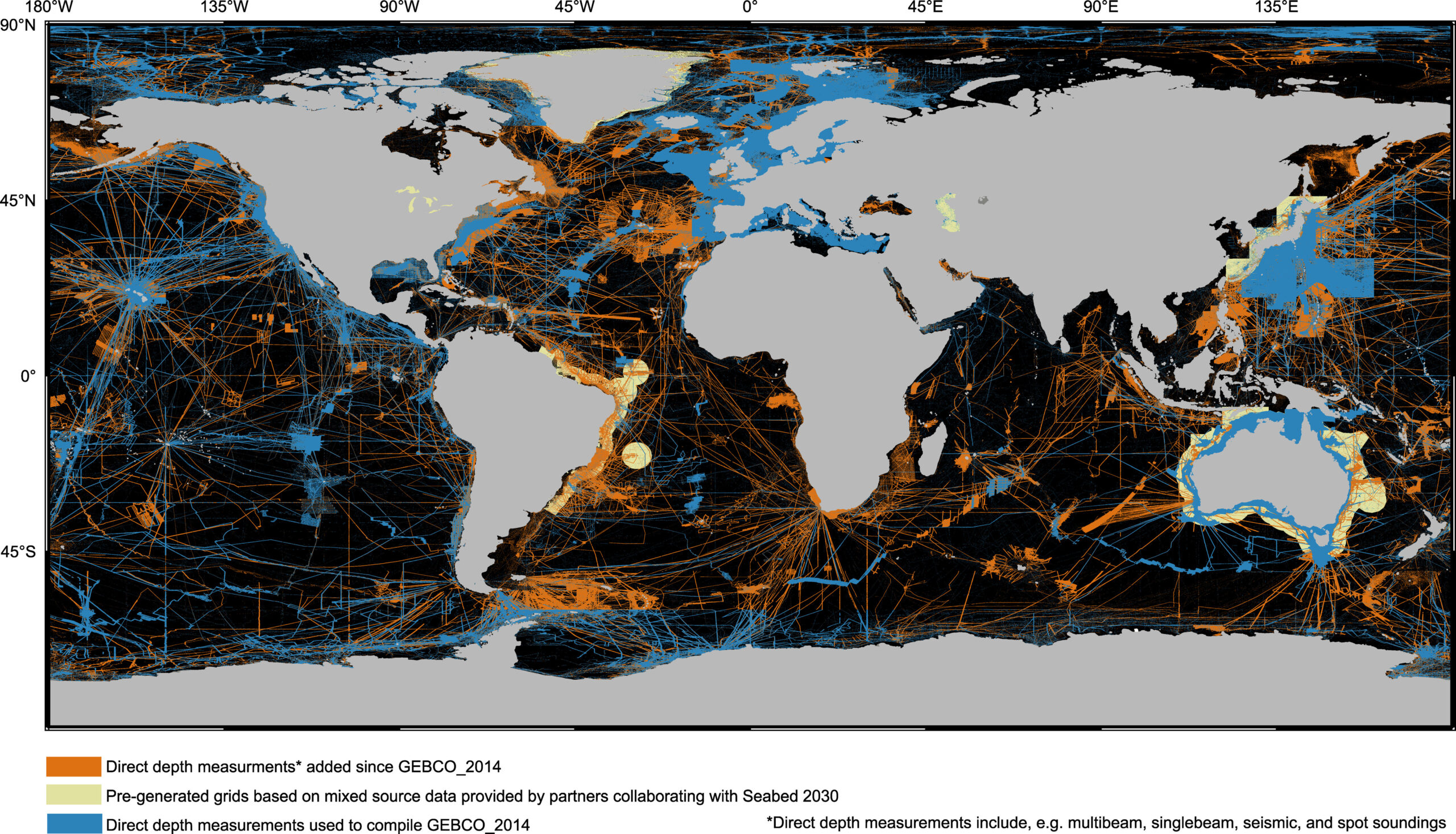

This combination of the need for a comprehensive seafloor map supporting a sustainable ocean and planet, and the recognition of the profound lack of seabed knowledge, led to another great initiative. In 2017, the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 project was established to accelerate GEBCO’s mission and complete the mapping of the seafloor by 2030. The vast majority of our seafloor will be considered mapped if one depth sounding exists in an area of 400 by 400 meters. The Seabed 2030 standard requires closer-spaced soundings in shallower waters, though never more than one sounding in an area of 100 by 100 meters. During the project’s first five years, data sharing and ocean mapping mobilisation efforts have quadrupled the area covered by directly measured depth soundings. And still, we are only at the beginning, as over 75 % of the seafloor remains unmapped.

Crowdsourced data collection, or citizen science, has long been around in many fields and now contributes to global ocean mapping efforts. Crowdsourced bathymetry is getting more widely accepted and recognised by the established mapping community, including hydrographic offices, and has the potential to be scaled up many times. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) Crowdsourced Bathymetry initiative is gaining momentum and attracting more and more interest from a growing and wider public. While a few years ago, bathymetric data collection was limited to a few established players, we are now seeing a broad range of contributors. Research vessel operators, cruise ship operators, commercial survey ship operators, fishers, super yacht owners, and leisure boat equipment manufacturers are growing more aware that they can contribute to seabed mapping and are increasingly willing to do so.

Seabed mapping sensors are put on autonomous platforms that can operate for longer periods with near zero carbon footprint, without the complexity of carrying a crew, and, once scaled up, at a reduced cost. In addition, green laser systems on airborne platforms, including drones, show improved data quality results in coastal zones and bathymetry derived from satellite imagery is being exploited as a potential source of depth data where water clarity permits.

The global paucity of depth information is stifling ‘the science we need for the ocean we want’, which means that decision-making by governments and multilateral institutions is without the benefit and consideration of all the evidence required. It is now well-accepted that bathymetric data is essential as a baseline for characterising the ocean environment and its systems. But in addition to scientific and rational justifications, we can ask ourselves the following question:

Do we not have an obligation to humanity to complete the work of our adventurous ancestors, like Leif Eiriksson, Admiral Zheng He, Jean Baret, Marie Tharp and Bruce C. Heezen, to discover the remaining part of our planet? After the 2nd World War, humankind’s inquisitive nature and technological advancements shifted towards outer space. But, in the recent words of Bill Gates: ‘Space? We have a lot to do here on Earth.’

Only two per cent of the total global research budget is ocean-related. Therefore, getting governments, science, and industry to work together towards improving ocean knowledge and completing the mapping of our planet is the main task of GEBCO.

GEBCO is unique. It is one of the building blocks needed to improve ocean literacy, understand how our ocean influences life on earth and, vice versa, understand how humankind influences the health of our ocean. GEBCO also invests in the future of our ocean through the GEBCO Training Program, funded by the Nippon Foundation. This highly successful training program is currently in its 19th year, having delivered over 100 students from more than 40 countries, where 90 per cent of them are working in ocean mapping. The GEBCO Guiding Committee recently established a new GEBCO Sub-Committee on Education and Training to coordinate more effectively with the current training program and reach out to other ocean mapping programs so that GEBCO has the interest of and can be managed by future generations.

GEBCO is strongly supported by its two parent organisations, the IHO and the International Oceanographic Commission (IOC), and thus by all the hydrographers and oceanographers of the world.

GEBCO is the only publicly available, authoritative, global, compiled bathymetric dataset that is more and more widely used by a diverse group of users.

But most of all, GEBCO is a network of voluntary, passionate, professional people, ocean scientists, hydrographers, and industry representatives, working towards the same goal, to finish Earth’s last great mapping endeavour.

Evert Flier

Chair of the GEBCO Guiding Committee

- Carpine-Lancre, J., Fisher, R., Harper, B., Hunter, P., Jones, M., Kerr, A., Laughton, A., Ritchie, S., Scott, D. and Whitmarsh, M. (2003). The History of GEBCO 1903-2003: the 100-year story of the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans. Lemmer, Netherlands. GITC bv, 140pp.

- GEBCO (2023). Maps of world ocean bathymetry. GEBCO The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, British Oceanographic Data Centre (BODC), National Oceanography Centre, United Kingdom. https://gebco.net/data_and_products/printable_maps/ (accessed 7 October 2023).

- https://gebco.net/data_and_products/historical_data_sets/#gebco_2022 (accessed 7 October 2023).

- GEBCO Bathymetric Compilation Group 2023 (2023). The GEBCO_2023 Grid a continuous terrain model of the global oceans and land. NERC EDS British Oceanographic Data Centre NOC. https://doi.org/10.5285/f98b053b-0cbc-6c23-e053-6c86abc0af7b